Is RRR a Primary Policy Tool for China?

The Chinese People’s Bank cut its one-year lending rate for the second month in a row, following the steps of its West colleagues, albeit at a slower pace.

The ECB and the Fed eased credit conditions in September, forcing other large Central Banks to follow suit. The interest rates cuts without clear risks of severe downturn but in response to soured trade relations can be considered as a competitive devaluation of national currencies to support export activity. This is an example of trade protectionism, but from central banks.

By lowering the rate by 25 basis points (the result of the vote was 7–3), the Fed gave a signal that it was no longer going to satisfy the whims of the markets — none of the officials expected further rate cuts. As expected, there was discussion about the persisting REPO market issues, but Powell assured that everything was under full control and there was no reason to worry. Powell’s comment about the need for “organic growth” of assets on the balance sheet (which means low excess reserves do worry the policymakers) was puzzling, because anytime excess reserves are increasing (liability side) it should be equaled with respective increase on the asset side (buying more Treasuries or MBS). After all, “organic growth” is still a signal about QE and, as a result, pressure on the dollar increased.

For PBOC, going in stride with global Central Banks is only small part of the task. The monetary policy also aims to adjust the growth path of the Chinese economy, which is expected to approach the lower border of the target range of 6.0% - 6.5% this year.

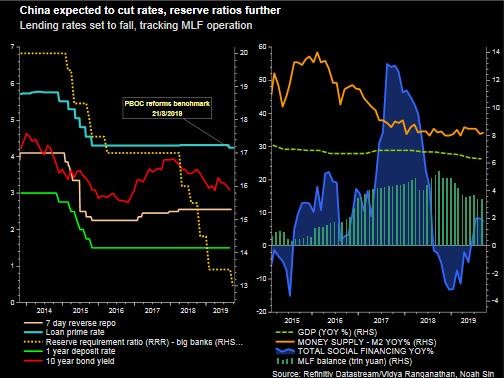

The prime loan rate was reduced by 5 basis points on Friday to 4.2%, the second time in a month and just a few days after the next decrease in the reserve ratio for banks came into effect. Thus, PBOC chooses a series of small, targeted measures instead of “swinging a sledgehammer” of the big policy rates, hoping that this will limit high-risk investments and overheating in the real estate market.

In the chart on the left, you can see that the reserve ratio remains the most active policy tool for PBOC, which has dropped from 20% to 13% in about four years. It is also worth noting that China, unlike the West, is not trying to determine money market rates (for other economic agents), and then keep them in the corridor through deposit-lending operations with banks (repos, reserve on excess reserves, etc.). Therefore, they can be extremely volatile. Instead, PBOC seeks to directly impact the pace of credit creation by setting required reserves ratio, i.e., because it sets the target rate of credit expansion. This is an example how banking systems tends to work when administrative control takes over market equilibrium paradigm. As you know, the maximum amount of lending in the economy is limited by the monetary base times 1 / reserve ratio (aka credit multiplier).

The push in economic activity from lowering the same prime rate is expected to be modest. Bank customers, at best, will receive a loan rate reduction of 11 base points, which is more than half that of a reduction in the United States. The five-year loan rate, which is used as a benchmark for the mortgage rate in China, remained unchanged at 4.85%.

Experiments with “secondary” rates show that PBOC remains open to credit expansion, but so far, the risks of overheating prices in some markets outweigh the beneficial effect on economic activity. Nevertheless, the stimulating policy mainly consists of fiscal measures, the most ambitious of which was the reduction of taxes or reliefs for municipal governments in attracting financing for infrastructure projects (municipal bonds for “special purposes”).

Please note that this material is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice.

Disclaimer: The material provided is for information purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice. The views, information, or opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, and not to the author’s employer, organization, committee or other group or individual or company.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

High Risk Warning: CFDs are complex instruments and come with a high risk of losing money rapidly due to leverage. 72% and 73% of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs with Tickmill UK Ltd and Tickmill Europe Ltd respectively. You should consider whether you understand how CFDs work and whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

Futures and Options: Trading futures and options on margin carries a high degree of risk and may result in losses exceeding your initial investment. These products are not suitable for all investors. Ensure you fully understand the risks and take appropriate care to manage your risk.